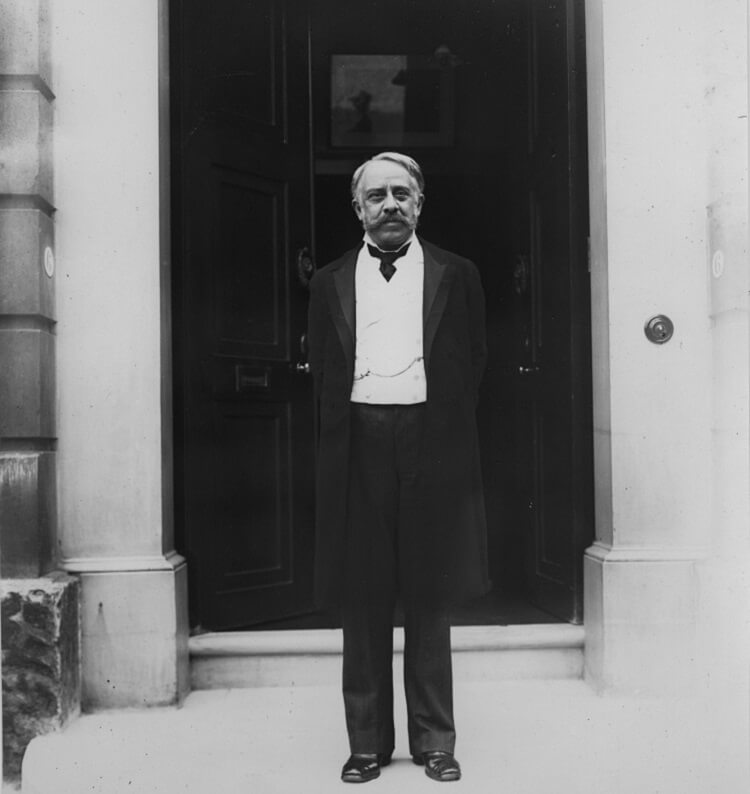

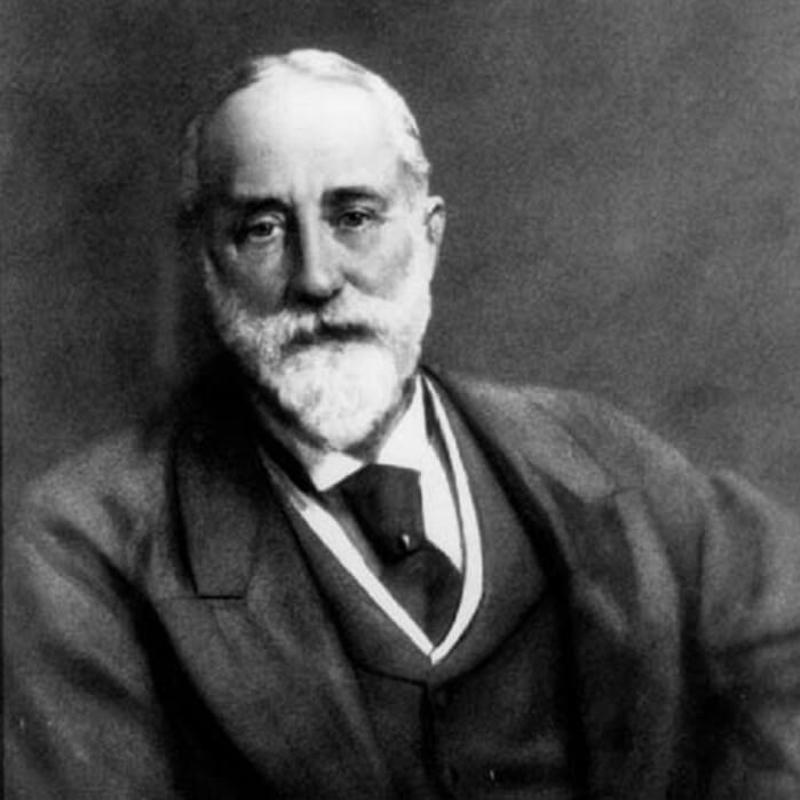

William Chandler Roberts-Austen

Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen outside the Royal Mint at Tower Hill.

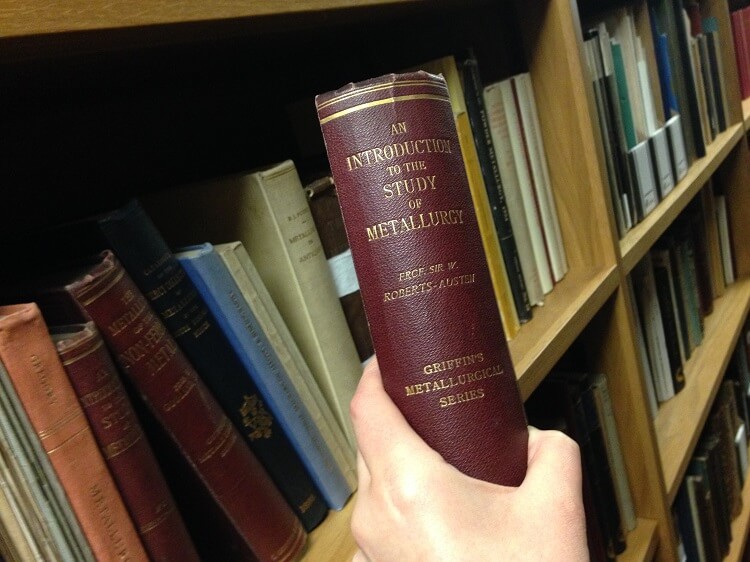

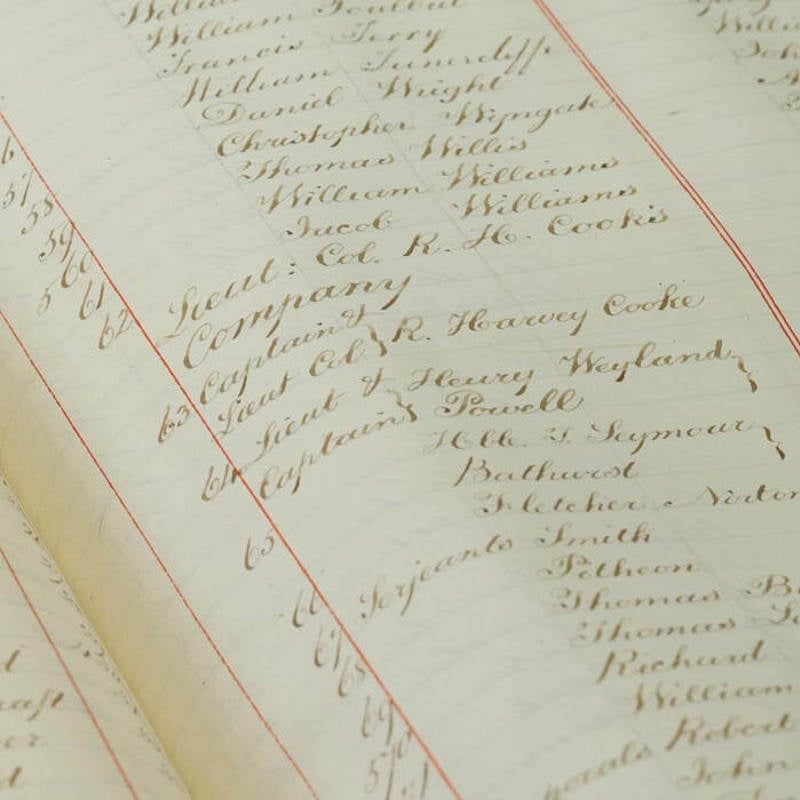

The Museum library houses a collection of books that were originally used or written by Royal Mint employees. These cover a wide range of specialist subjects such as chemistry, metallurgy, photography, art, engraving, construction and business management. The content of the library echoes the Museum’s object collection in that it documents not just the products of the Royal Mint but the whole organisation, providing a textual history of the minting industry.

Numerous works can be found on Sir Issac Newton, the most famous Master of the Mint, or engraver Benedetto Pistrucci, designer of the St George and the Dragon Sovereigns of 1817.

Looking through the shelves, a few other names stand out as significant characters in the history of the Royal Mint who are perhaps not as regularly celebrated as they should be.

One of those characters is Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen (to give his name in its final form). He specialised in metallurgy, the science of the properties of metals and their production, and is the author of a considerable amount of papers in the museum. He was Chemist of the Mint from 1870 to 1882 when he became Chemist and Assayer of the Mint. He retained this title until his death in 1902. The Mint still carries out the important process of assaying today, checking the purity of precious metals to determine their quality.

The Royal Mint Museum Library. (As a conservation measure before the move, we have boxed vulnerable items and tied books with loose spines with strips of tyvek.)

In the 1870 Treasury reorganisation of the Mint, the forward thinking Deputy Master Charles Freemantle hired the young Roberts-Austen to rightly ensure that a high level of practical chemical knowledge could be utilized from within the Mint at Tower Hill. He was well placed for the job, previously having been assistant to the last Master of the Mint and renowned chemist, Thomas Graham. As Freemantle’s right hand man, Roberts-Austen was given the freedom to pursue the kind of pure research which raised the scientific stature of the Mint and aided the overall reform of the organisation under Freemantle’s management.

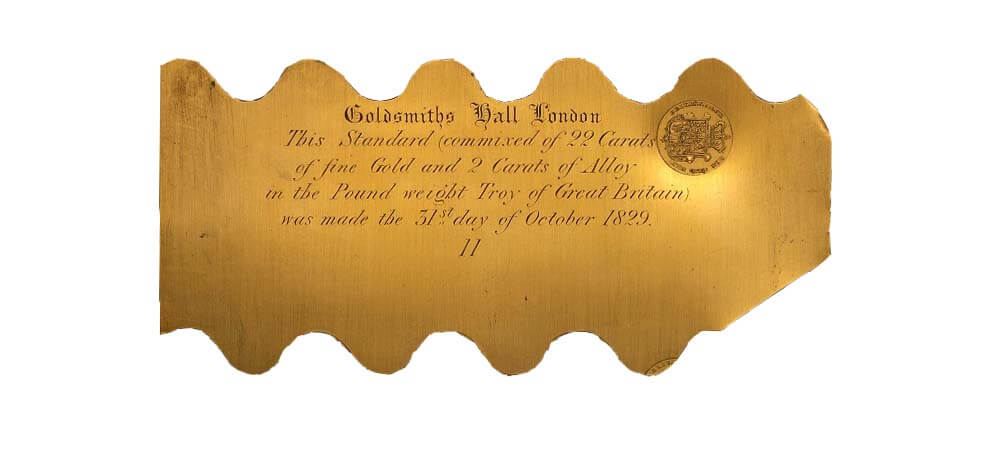

Roberts-Austen’s main focus was accuracy and his work led to greater consistency in the fineness of the coin. It was due to his attentions that the gold sovereign would be known as ‘the chief coin of the world’. One of his early contributions to the Royal Mint was creating a new set of gold and silver trial plates, after confirming his concerns about the accuracy of the current trial plates of 1829, a valid concern considering these were and still are the legal standards of reference for checking gold and silver coinage.

Trial Plate of 1829, proved to be inaccurate by Roberts-Austen. (Samples would be cut from this for the purposes of conducting assays.)

After carrying out tests, he judged that samples from these trial plates could not be trusted, as materials in the alloys were not uniformly distributed. He made the case to Treasury to make the new plates from pure gold and silver. They were produced in 1873 and then verified by Goldsmiths’ Company, a reversal of the previous practice. These plates were so accurate that they provided the standard not only for the coinage but also for domestic gold and silver plate.

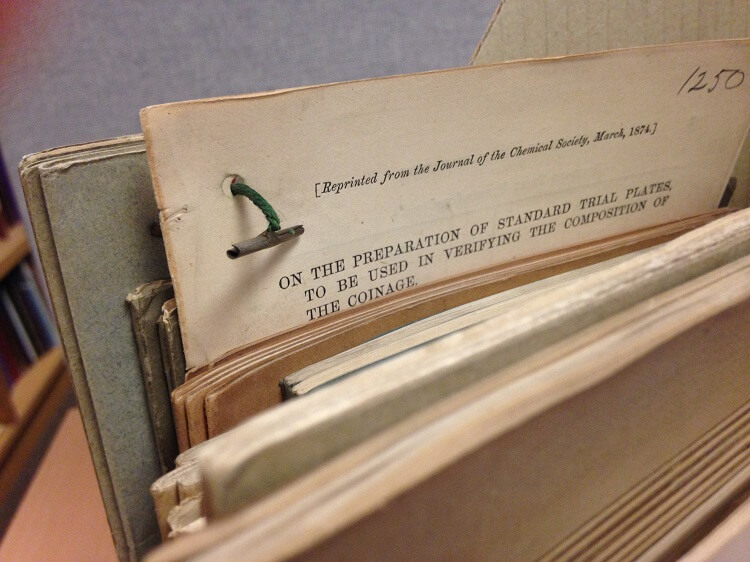

Papers written by William Chandler Roberts-Austen in the Royal Mint Museum Library.

From the writing of Roberts-Austen it can be understood that he took a special interest in refining the aesthetic quality of metals, influenced by the skill of the Japanese. Part of his memorandum in the Mint Report for 1897 is dedicated to describing methods of treating the surface of medals. His attention to this matter had been specially directed during the making of the Commemorative Medals issued for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. His remarks on the patination of copper medals were of particular interest and his experiments in this area led to highly satisfactory results. As a professor, he lectured widely on this topic of colours of metals used for artwork.

Versions of the Commemorative medal for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, in varying experimental colours.

Versions of the Commemorative medal for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, in varying experimental colours. The textbook ‘Introduction to the Study of Metallurgy’ (1891) ran to six editions and was very influential. A passage from this demonstrates Roberts-Austen’s passion for the visual effect of metals:

Take, for example, a mass of red copper and one of grey antimony; the union of two by fusion produces a beautiful violet alloy when the proportions are so arranged that there is 51 per cent of copper and 49 per cent of antimony in the mixture… unfortunately, it is brittle and difficult to work, so that its beautiful colour can hardly be utilised in art.’

Although a scientific account, the language used here is expressive and illustrates the concern for a balance of both beauty and practicality in refining the products made at the Royal Mint. Considering this aspect of his expertise, it seems most appropriate that Roberts-Austen was vice-president of the Society of Arts, as well as being member to various scientific institutions and a fellow of the Royal Society.

Commemorative Plaque of Sir William Chandler Roberts-Austen by Mint Engraver G.W. de Salles.

On 18 July 1899, Roberts-Austen, as president of the Iron and Steel Institute, personally handed Queen Victoria the institute’s Bessemer gold medal in commemoration of the progress made in the metallurgy of steel during her reign. He was knighted in the same year.

A permanent reminder of Roberts-Austen in the Royal Mint Museum is a painting which was hung in the dining room of his home at the Mint for many years, donated to the Mint in 1903 by Lady Roberts-Austen. 'The Queen's Shilling', by John Collier (c.1900) depicts the silver melting house with crucible and furnace.

'The Queen's Shilling' by John Collier.

The results of Roberts-Austen’s work had wide industrial application, as did his automatic recording pyrometer, a device that he invented in order to make precise measurements of temperature changes in furnaces and molten metals. At the time of his death, Roberts-Austen was in the top job, as interim Deputy Master of the Mint. Obituaries illustrate him as a great personality as well as a great intellectual, and past accounts from Mint employees describe him as a practical joker and an excellent mimic. An eminent figure, not only in the history of the Royal Mint but in the greater scientific community, we are proud that so much of Robert-Austen’s legacy remains in the Museum collection.

You might also like

The Royal Mint Advisory Committee

The Committee was established in 1922 with the personal approval of George V.

Charles Fremantle, Deputy Master of the Royal Mint 1868-1894

A key figure in the history of the Royal Mint.

Counterfeits and Cautionary Tales

For as long as there have been coins there have been counterfeits.

Library and Archive

The Royal Mint Museum contains a valuable numismatic library of some 15,000 volumes.